There are a lot of different paths you can take to get to a net-zero home. Everything from passive homes to earthships to modular and factory built houses. You can retrofit an existing building or you can build a new one. All of the options can make your head spin and there are pros and cons to each of them. In my case, I’m building a new, factory built net zero home, which has been in the planning stages for a while now, but is scheduled to start construction very soon. I thought it would be interesting to share what I’m doing and why my wife and I chose the path we did. So let’s see how we came to our decision … and if I have any regrets so far.

Before I get into exactly what I’m doing for my new house, there’s a little context I think is important. One of the reasons I named my channel, Undecided, was because I have a lot of different interests. I’m very curious and like to learn new things and try to keep an open mind. It goes back to when I was a freshman in college and hadn’t declared a major yet. At my college if someone asked what your major was in that case, you’d answer, “I’m undecided.” If you’ve been watching my videos for a while, you may have noticed that I go through waves of topics. Starting a couple of years ago I began publishing videos on different net zero and sustainable home building techniques. That was me following different threads I found interesting and concepts many of you were sharing with me. As I learned and shared what I was finding, I got motivated to do some of those building techniques on my own home.

I see two main motivations for wanting a super energy efficient home. One of which shouldn’t be surprising if you’re concerned about the environment. In the US in 2020, carbon emissions from the residential sector equated to about 6.1% of total greenhouse gas emissions. The European Union and U.K.’s residential sector had a greater share compared to the U.S. at about 12%. Although the shares don’t look that relevant compared to the emissions from other sectors, the amount of CO2 emitted in both regions went above 360 million metric tons of carbon dioxide.1 2 The other big motivator for high efficiency homes is saving energy and ultimately, money (at least in the long run). These reasons aren’t mutually exclusive, and you most likely have one or both of those motivations if you’re considering going net zero. For me, I’m interested in both of those points … and I want to be financially responsible in going net zero. Of all the concepts I’ve covered, like retrofits, passive house standards, earthships, and modular and factory built homes, there are two that jumped out at me when we started thinking about a new home: that’s passive house and factory built homes.

Just for a quick recap, comparing a passive house to a standard built home: the passive house can save up to 90% of the energy used for heating and cooling without cutting back on comfort. 3 4 5 6 7 8 You can check out my Passive House video if you want to get all the details, but in short, there are very specific and rigorous benchmarks you have to hit on space heating, electricity consumption, air tightness, and more. For instance, on air tightness you can’t exceed 0.6 air changes per hour at 50 pascals of pressure.3 9 For a point of comparison, a typical house might have 3 – 6 air changes per hour.10

While I’m interested in passive houses, I wasn’t completely on board with all the hoops you have to jump through for official certification. The primary advantage of certification is strict quality control. The first and most crucial step to getting this accreditation is finding a competent Certified Passive House Designer or Consultant and incorporating them into your process as early in the design sequence as you can. Then, with the help of your contractor, you’ll decide which certification you want to get — in the U.S., for example, there’s two certification bodies: the Passive House Institute (PHI) and the Passive House Institute US (PHIUS). Yeah, that’s not confusing at all. Basically, it’s two groups that disagree on the “right” way to build a passive house. In general one isn’t necessarily easier to get than the other one, but PHIUS is considered a little more adaptable than PHI.

With the certification goal defined, it’s time to run a detailed digital simulation of the building’s performance — this is called an Energy Model. It will help to define aspects like window glazing, shading, construction type, ventilation, and more by providing details on heat and airflow, moisture, noise, light, etc. And the model is constantly updated as the design team identifies changes that are needed based on the realities of the construction site. 11

After the home is built on the final site, the construction will be subjected to the ‘Blower Door’ air tightness test, which uses a fan to pressurize and depressurize the building while sensors are used to measure the quantity of air leakage through the house’s envelope. If your home does well in the test, there are documents to be submitted to get your house certified.

I’m not against any of that, but this is where going the modular or factory built route comes in.

I’m sidestepping a lot of the certification craziness because I’m working with a company that’s hitting many of the passive house standard’s benefits, but without the need to strictly follow the standard. For me the most important criteria was reducing thermal bridging in the structure, having ample insulation to hit extremely high R-values for the walls, roof, windows, and foundation, as well as being airtight to control air leakage. I’ll be going much more in-depth on the actual construction process in a future video, but I’m working with the company Unity Homes, which is a sister company of Bensonwood Homes.

They have a modular approach to their house design to reduce the amount of custom design and engineering required for each project. Basically, they’ve already taken care of all of those pre-planning, engineering, and modeling steps. Also, building the walls and structure in a climate controlled factory setting speeds up construction and reduces waste. I’m still working out the details with Unity, but I should have videos coming up showing the entire process within the factory, as well as the construction on site. The reason I’m not too concerned about getting official passive house certification is because of Unity’s track record and design. They’re houses achieve near passive house level results. I’m going to be doing the door blower test on the house immediately after onsite assembly and later on in the finishing stages to make sure I’m hitting an ACH below 1 … ideally 0.6 or below.

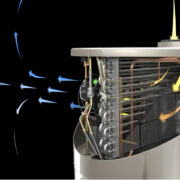

That brings me to the HVAC system I’m going to be getting installed, which will be a WaterFurance geothermal setup with a desuperheater to produce hot water. A desuperheater basically strips away a small amount of heat from the geothermal system to help produce the hot water in a very energy efficient way.

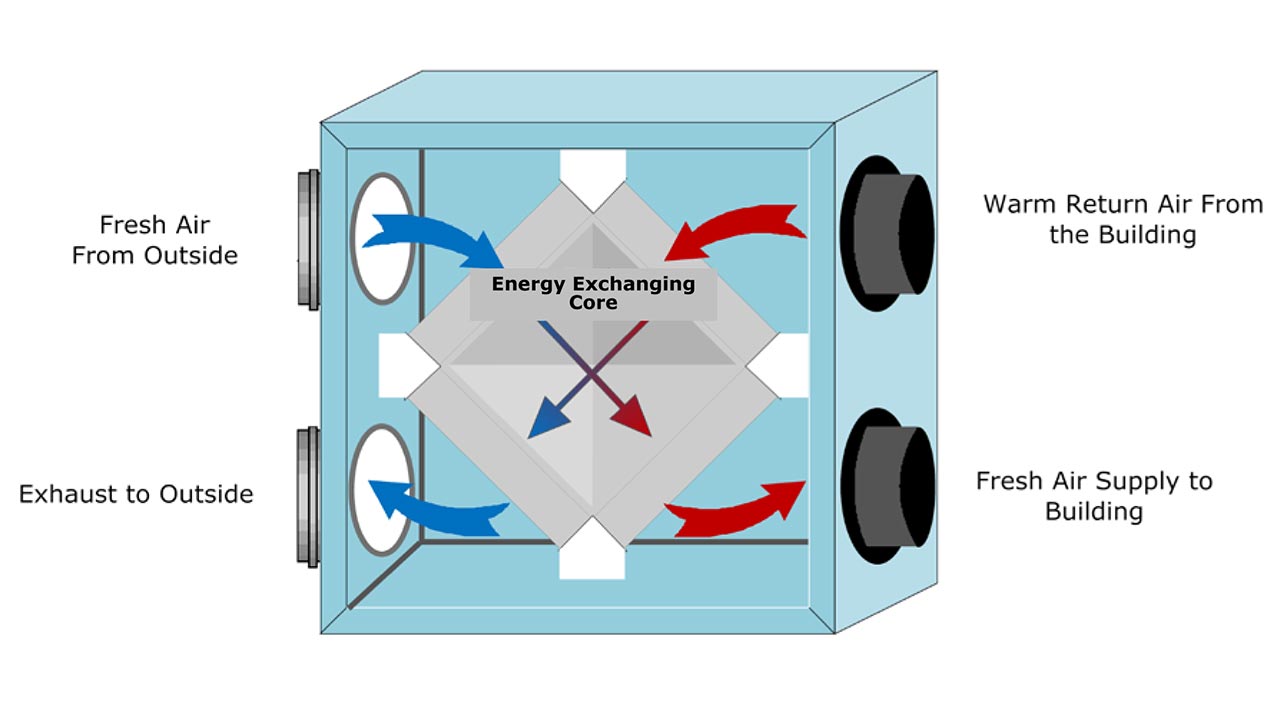

Some of the benefits for striving for a passive home are that they have cleaner and fresher air since the air intake and exhaust are tightly controlled with an energy recovery ventilator (ERV), which my house will also have. It exchanges fresh outside air with stale inside air and recovers the heat in the process. It’s a little strange, but I’m probably the most excited about the ERV setup in my house. I suffer from pretty bad seasonal allergies and with systems like this and extremely airtight houses, it can provide some excellent allergy relief.

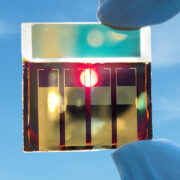

Okay, I may have lied. I’m actually as excited about hitting net-zero as I am about indoor air quality. Net zero is when a house generates as much energy as it uses over the course of a year, which means solar panels and, in my case, a battery system. I’m still hashing out the exact details of the system, but it will most likely be a 15-18 kW solar panel array with 15-20 kWh of battery storage. It’s a little difficult trying to model our energy requirements before we’re actually living in the house to see what we need, but it may be the type of thing where we add onto the existing system a year or two down the road if we’re falling short on our net-zero goal.

And for homeowners interested in getting solar, Energysage is great and you should use it, but I’m actually working on my own complementary project that will be launching soon (not exactly sure when yet), but it’s meant to help demystify getting solar for your home and answer a lot of questions. The goal is to pass along what I’ve learned over the years so you feel confident in your decisions on getting solar and achieving your goals. If you’re interested in being part of the beta launch group, you can join the waitlist at the link in the description.

And for long time followers of the channel, it won’t be a surprise to hear this, but I’m going to be building out a pretty extensive smart home. I have plans for smart shades and blinds to help control how much sunlight and heat comes into the house at different times of the day and year. Smart controls for the HVAC system and lights, a smart electric panel, as well as a pretty extensive home network and security camera setup. I’m a big believer in smart homes and how the internet of things can benefit a home’s energy efficiency. Again, I’ll have more videos coming down the line on what exactly I’m doing there.

But will all of this be worth it? Obviously, the jury is still very much out on my specific build, but passive homes, and energy efficient homes in general, can provide a lot of value. It can vary greatly depending on where you’ll be building your passive home. For example, in Salem, Oregon in 2010 a new 1,885 sqft² (175 m²) passive house project had a building cost of $159/sqft² ($1,711/m²) — about $300,000 in total — while the average price per sqft² in the U.S. at that time was $84/sqft² and a single family home in Oregon at that time cost about $250,000. Even though their passive home cost about 16% more than a conventional home, the energy savings for just heating was estimated at $800 per year.12 13 14 All of this is highly dependent on where you live and are building.

It’s not that different from getting solar panels for your home. In that case you’re basically prepaying for your electricity for the next 20-30 years. While it’s a little pricey up front, you’ve locked in your costs and will benefit from that over time. A passive house is the same thing. I’ll be paying more up front, but will benefit from the energy savings of the house over time. How much is the big question, especially because we’re building at probably the worst possible time. The prices of building materials and labor have increased dramatically over the past couple of years.

While building new was the right fit for my wife and I, it’s not a requirement to get a passive or net zero home. There are also certifications for retrofitting old construction that you can try and get. Since it’s not always practical to renovate old buildings to the Passivhaus Standard, the Passivhaus Institute created EnerPHit, which performs an analysis of Passivhaus components for retrofits. 15 16 17

Like a brand new passive home, a retrofit house offers high energy efficiency, thermal comfort, and healthy air circulation. In addition, older buildings offer more possibilities for energy savings and corresponding reductions in CO2 emissions because they use more energy than the typical new build. Some EnerPHit reports show a 93% reduction in energy loss for retrofits. 18 But, there are also challenges in Passive House refurbishment, such as conservation and external insulation issues, as well as space limitations for both internal insulation and ventilation systems. 19 You don’t always know what you’ll find on any home retrofit until construction starts, so costs can easily balloon. It’s one of the reasons we opted to build new instead.

However, a good friend of mine is going the retrofit approach on his house. It’s going to be fun to see how both of our projects compare as we progress. If you haven’t seen what Ricky Roy is up to on the TwoBitDavinci YouTube channel, here’s a quick rundown of what he’s doing.

“I’ve decided to retrofit an older house. And the main reason for this is because where we live, there weren’t that many open available lots. And for school districts and stuff, we were kind of forced having young kids to pick a place around here. So this is the best that we came up with. Now we’re going to have some challenges that Matt will not. For example, the house is very poorly insulated, so we’ll have to rip out all the drywall, get behind the studs and check out the piping, the plumbing, electrical, and definitely insulate the house better. Being in San Diego, most homes back in that era just weren’t insulated very well. The weather here is not as bad as Matt has to face, and so as a result, they kind of skimped out on that.”

“Another problem is our roof needs to be replaced in the next three to five years. And so, as a result, we can’t put solar panels on there. Instead, we’re going to go with a ground mount system off in the corner. So we’ll make videos about that. But the big difference, I think, between the two of us is going to be logistics, because we’re going to have to plan when to do these projects and find a way to do it without losing our minds, because we’re going to be living here while we do it. Matt and I will also be covering some of the same technologies like geothermal HVAC systems, for example, and for him, he’ll know exactly where it’ll be and placed. And for us, we’ll have to figure out where to do it and what to do about it. So depending on what kind of a viewer you are and what kind of house do you have, you’ll probably learn a lot from both of us, so definitely subscribe and stay tuned for both channels. And we’ll have a ton of content coming in the near term.” -Ricky Roy

I’m pretty excited to see how his house turns out. Be sure to follow both of our projects because it should be a fun comparison.

So … do I have any regrets so far? Only one: the timing. My wife and I are building our dream home and are settling in for the long term, which is why we’re willing to go a little above and beyond on the upfront costs for the long term benefits. This house should be low maintenance, low operational costs, and be more comfortable and healthy than any house we’ve lived in before. But again … the timing. Between the pandemic and inflationary pricing, it’s jacked costs up much higher than we originally expected, but those costs are across the board no matter what you’re doing right now. Should we have waited? I don’t think so. If anything, we probably should have started this project sooner than we did. That’s my regret, but I’m really excited to see how this turns out and to share it with all of you.

- U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions by Economic Sector, 2020 ↩

- Residential carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions in the European Union from 1990 to 2020 ↩

- What is a Passive House? ↩ ↩

- What is a Passive House? ↩

- Passive house ↩

- The History of Passive House: A Global Movement with North American Roots ↩

- The Benefits of Passive House Buildings ↩

- Energy efficiency of the Passive House Standard: Expectations confirmed by measurements in practice ↩

- Passive House certification criteria ↩

- “Airtightness in old buildings” ↩

- HOW DO YOU GET A PASSIVE HOUSE CERTIFICATION? ↩

- Passive House Energy Savings ↩

- Average price per square foot of floor space in new single-family houses in the United States from 2000 to 2020 ↩

- Single Family Home Prices – Portland MSA (Oregon part) ↩

- Criteria for the Passive House, EnerPHit and PHI Low Energy Building Standard ↩

- The EnerPHit Standard: How does it PHit in? ↩

- Overall retrofit plan for step-by-step retrofits to EnerPHit Standard ↩

- What is EnerPHit? ↩

- The new Passivhaus refurbishment standard from the Passivhaus Institute ↩

Hey Matt.. Could you do a video on commercial refrigeration? I work in a store and we have walk-in cooler rooms with no doors! The cold air blows out and we have a heater outside them to keep them from cooling the rest of the store. Not only that, but almost every grocery store I know of has open refrigeration units, which I understand are not very efficient, I understand closed units are better, even though they run a periodic defrost cycle to keep the windows clear. Also, I am not sure that there is a commonly agreed upon refrigerant which has a low GFP.. global warming potential. Perhaps ironically, CO2 is one candidate, but I understand it necessitates a double cooling loop.. there is a Loblaws store in Scarborough, Canada which uses this technology: (https://www.nrcan.gc.ca/sites/www.nrcan.gc.ca/files/energy/pdf/Loblaws-Scarborough_EN.pdf). I would really like to learn more about this subject and to have some insight as to where the technology is headed.

Interesting suggestion. Adding it to the list to look into.