Today is a really hot topic: water heaters. No, it’s not sexy, but water heater technology is kind of ingenious with its simplicity. A typical electric water heater has two heating elements; one near the bottom and one near the top, all housed in a very well insulated cylinder. As cold water is fed in near the bottom of the tank, the hot water is pushed out near the top. It’s also pretty simple efficiency-wise. For each unit of electricity that’s used, you get one unit of heat energy added to the water.

However, my water heater is wearing one additional piece of technology on top … like a hat. It’s a heat pump. That means for every unit of electricity I’m spending I’m getting 3 to 4 units of heat added to the water. It’s way more efficient than any electric or natural gas water heater you can get, but hybrid heat pump water heaters have some quirks and challenges. Also, my setup is a little unique … like … what’s that strange mini-me version of a water heater sitting next to it?

I keep saying, “heat pump all the things” and I’m not kidding. When it comes to energy efficiency you can’t beat a technology that seems to break the laws of physics. Generating more heat energy than the amount of energy you put into it seems like a magic trick, but it’s not. I’ve got a 50 gallon Rheem Proterra hybrid water heater here. I’ll be sharing my thoughts on this specific model as we go, but this is more about just using a heat pump water heater in general. Brand doesn’t matter, but I’ll be getting to the quicks and downsides in a bit.

So why go with a heat pump water heater?

The biggest reason you’d want a heat pump version is for exactly the reason I mentioned already. It’s mostly about the Coefficient of Performance (COP). That’s the ratio of energy in vs. energy out … or more simply how much heat energy you get for every kW of electricity or natural gas therms you put in. Just for clarity, because I’ll be getting into comparing my old natural gas water heater to this new one, one therm is the energy content of about 100 cubic feet (2.83 cubic meters) of natural gas.1

The massive boost in COP is the big selling point of heat pumps in general. You’ll be spending far less energy and money, in theory, to create hot water for your home. It’s a very appealing sales pitch. However, this is where some of the downsides start to creep in, or at least the perception issues start to creep in.

What about the downsides?

The first potential pitfall is the cost. Heat pump hybrid models are just more expensive than straight electric or natural gas models. In my old house, we had a 40 gallon natural gas model that cost about $800, not including installation. The Rheem I have now retails for around $1,500 plus installation, so there’s a sizable jump in cost. However, there are rebates and incentives available in most places to help knock that cost down. Sometimes those rebates come from the state or your local utility company, so it’s best to do your due diligence before you make a purchase. In my case, here in Massachusetts, there’s the MassSave program which will cover $750 of that cost.2 The best part about that one is that it’s usually available as an instant rebate when you buy the water heater. So, suddenly that $1,500 is now $750. There’s also a federal tax credit of up to 30% (which is capped at $2,000) off the full installation (after local rebates have been applied). So if the total including installation was $2,500, here in Massachusetts you’d end up paying about $1,225 (eg. original cost: $2,500 – $750 in state rebates – $525 in Federal incentives). Bottom line: in some cases it can be equal to or cheaper than a standard water heater depending on what rebates are available in your area.

The other couple of common elements that I see brought up a lot are: noise and recovery time. When it comes to the noise issue, your mileage will vary wildly by brand, model, and sometimes the luck of the draw. In my case, I haven’t noticed any significant noise issues at all. I have an insulated mechanical room that’s not too far from the main living room area and I never hear the water heater running. However, I do hear my HVAC system ramping up and down. I have heard from others that they’ve had some noise issues with this exact model of water heater, so be aware. A friend of the channel, Paul Braren, has some great articles on his website about this.

As for recovery time, which is a measure of how quickly it can heat cold water back up, it’s also been a non-issue for me. In fact, I’d argue that this is largely a myth that heat pump water heaters have a slow recovery time. It’s going to depend on how much hot water you use and what settings you have on your water heater. For this Rheem, there are a few different modes you can put it in: Energy Saver, Heat Pump, and High Demand. Energy Saver is the default and what I’ve been using. On this setting, it fully utilizes the heat pump compressor for the best COP possible, but also incorporates the electric heating elements for high demand and recovery needs. It’s a balanced approach. The other two modes are what you’d expect. “Heat Pump” is full on heat pump only, which can affect the recovery time and can even increase energy consumption, according to Rheem. “High Demand” mode puts more emphasis on the electric elements and also increases energy consumption. I’ll get into what I’m actually seeing in just a minute.

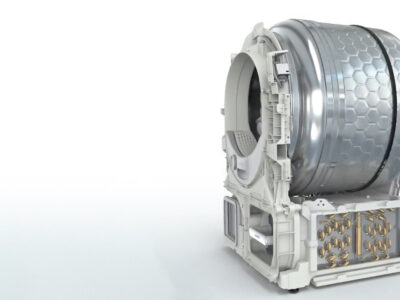

The final potential pitfall of a heat pump water heater is space … and I mean physical space. Because they have an air source heat pump strapped to the top, like a hat, they need a certain air volume in the room they occupy. The way the heat pump works is that it passes the room’s air through a heat exchanger to extract the heat into a working fluid. That fluid is then sent through a compressor and turned into vapor, which circulates through pipes snaking around the water heater, making hot water. As the heat is extracted back out of the working fluid it cools off, turning back into a liquid, and ready to repeat the cycle. The side effect is that the air that’s getting ejected from the heat exchanger is cool and dry. If the room’s volume is too small, the heat pump will lose efficiency as all the usable heat is extracted from the room’s air.

This is VERY noticeable in my setup. My mechanical room is technically too small. You need about 700 cubic feet, but my mechanical room is only about 600 cubic feet … and that doesn’t account for all the equipment inside it taking up space. It’s probably closer to 450-500 cubic feet. When we first moved into the house, the mechanical room felt like a meat locker when you opened the door: in other words, very cold. There are ways you can vent the water heater to alleviate this issue, but we opted to not do that … at least not yet.

The reason? That little mini-me tank sitting next to the Rheem is why. I have my water heater tied into my geothermal HVAC system that’s heating and cooling my entire house. The excess heat from that system’s compressor is captured into water that sits in that tank waiting to be used by the Rheem water heater. That means our Rheem isn’t refilling itself with cold water straight from the outside — it’s refilling with water that is probably already over 110F. I really want to wire a sensor into the holding tank to track the water temp, but haven’t gotten around to it yet. Anyway, the end result is that my water heater doesn’t have to work as hard to get my water up to temp.

We didn’t get the geothermal desuperheater hooked up and working until we’d been living here for almost two months. After we did, I noticed that the mechanical room isn’t meat-locker cold anymore, but it’s still cool … which is cool.

What’s the reality so far?

That leads me right into the performance I’ve been seeing. So strap on your nerd hardhat, because I’m about to drop some numbers and charts right on your head. At this point I still don’t have a ton of data, but enough to start getting a sense of where this is going. Since we didn’t move in until August, I’m only looking at September through January and comparing this to the same months last year with our old natural gas water heater. If you’re curious, I had an Aquanta smart device installed on my water heater that tracked exactly how much gas we were using.

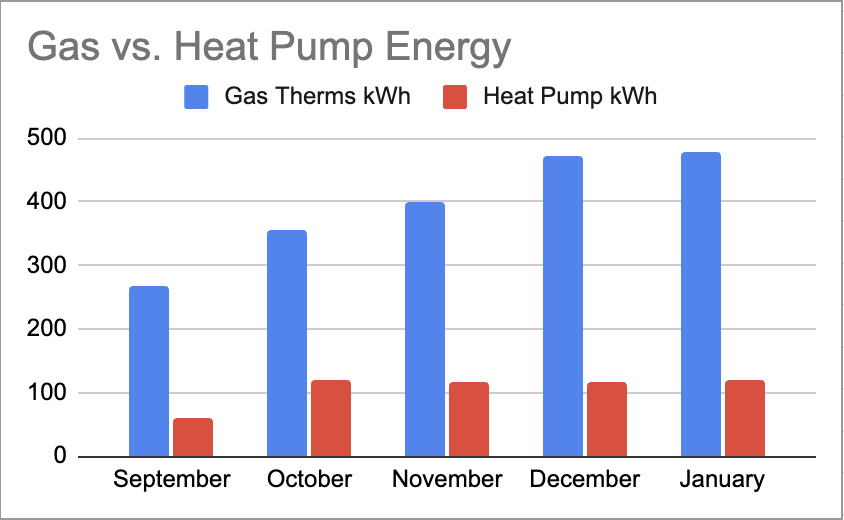

Gas Therms converted to kWh vs. Heat Pump kWh

For this first chart it’s the amount of gas vs. amount of electricity. You’ll notice that there’s a noticeable jump in October for both gas and electric because that’s when the cold weather really kicks in. December through February tend to be the highest use case months, so there’s another uptick noticeable for gas in December. What’s interesting though is that you can see our electricity didn’t jump in December. In fact, it’s slowly been declining each month since October. My hunch right now is that it’s because of the geothermal holding tank, which started up in October. It counteracted the typical increase.

Operational costs are another story though.

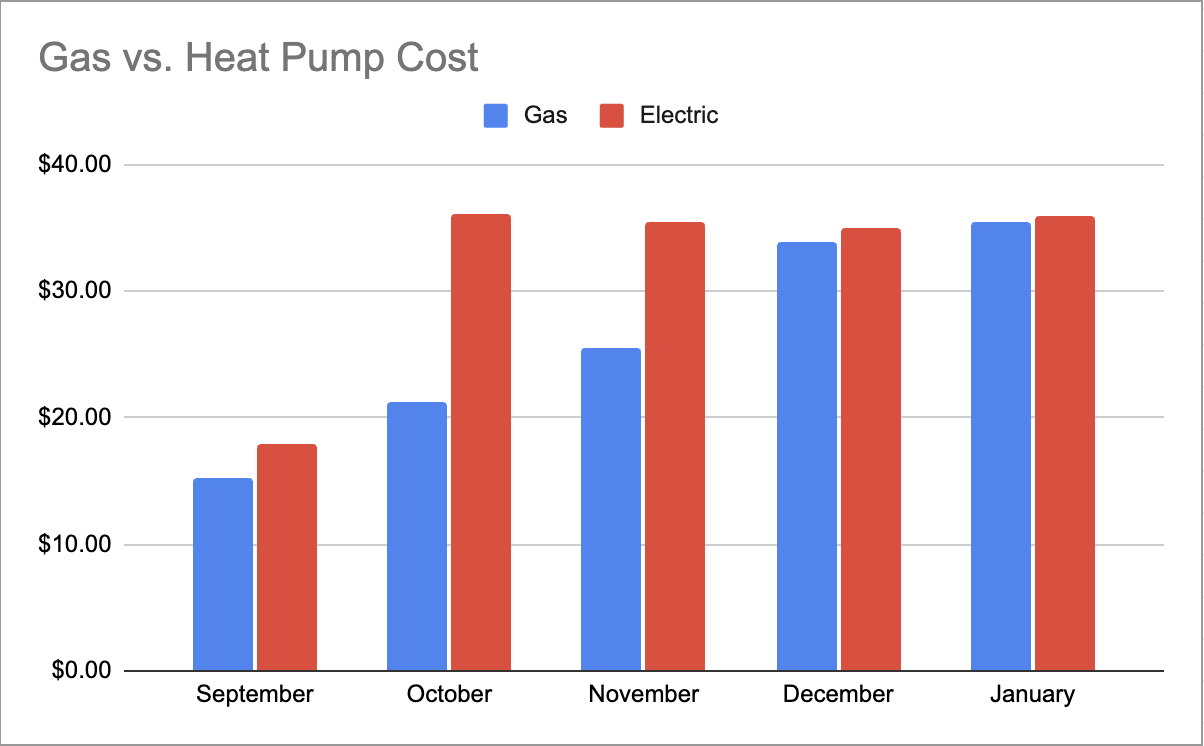

Gas vs. Heat Pump – My Costs

If you look at this chart, you’ll notice that gas and electricity are basically a wash in September and December, but electricity is dramatically higher in October and November. The reason? Gas and electricity prices in my area. Electricity in Massachusetts is very high. In fact, we boast some of the highest in the country. We’re paying around $0.30/kWh vs. gas which was coming in around $2.18/therm (at the time we were using it). The cost benefit is kind of a mixed bag in my area. Massachusetts electricity and gas prices mean this costs me about 22% more for hybrid heat pump hot water based on the limited data I have. I have a hunch that will change over the coming months because we’re still experimenting to find the best settings for us. We may still try venting the water heater, so it has more air to draw from. However, if you look at the national average cost of electricity ($0.17/kWh) and gas ($1.66/therm) and apply it to my usage, it’s a different story.

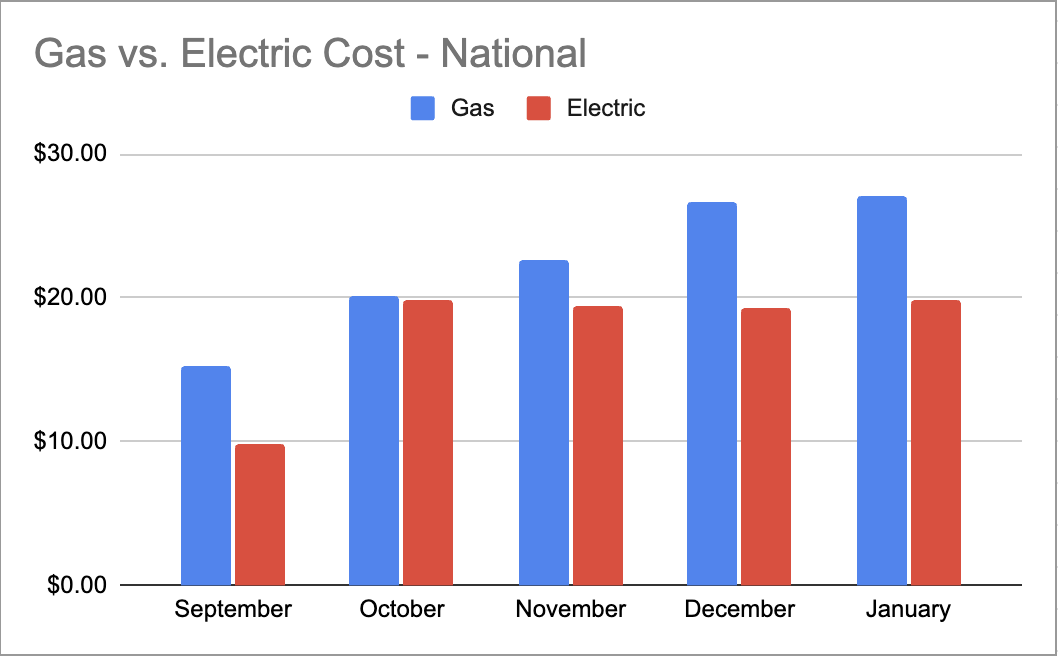

Gas vs. Heat Pump – National Averages

Electricity wins hands down across the board. Nationally it would cost almost 21% less to go with an electric heat pump water heater. Again … based on only a few months of my personal data.

I also have solar on my house, which is currently trending towards my goal of net zero energy from the grid over the course of a year. If that plays out, the actual cost of electricity to generate my hot water will be zero, which isn’t possible with natural gas.

Is it worth it to go with a heat pump water heater? Yes, in the vast majority of cases, it’s absolutely the best option out there. However, as you can see in my current data, it’s not completely cut and dry depending on what your electricity and natural gas prices are. If you’re already using a standard electric water heater, it’s a no-brainer to go heat pump. Again, upfront costs really aren’t that different right now with all the rebates available from utilities, state and federal rebates. In some cases, it can be cheaper to install a heat pump water heater … and then the long term benefits after that.

Comments