There’s concerns that homes with solar panels are reducing their utility bills at the expense of their neighbors without solar panels. The phenomenon is referred to as “cost shifting”: the idea that the credits utilities pay to solar homes for the energy they produce ultimately results in higher bills for customers without panels. This has had major implications on public policy…for better or worse.

So, is there any truth in the idea that the solar haves are making things worse for the solar have-nots? Who really benefits from residential solar, and how can we invest in renewables while keeping things fair?

Is the solar cost shift real?

This topic is one that’s been boiling around in the back of my mind for a while, but it’s bubbled up to the surface with some recent commentary I’ve been seeing online. It shouldn’t be a surprise to anyone that I’m a fan of solar technology for homes, communities, and the grid. I have it on my current house, and I’m installing it on my new one….so the “cost shift” has been nagging me. The more we dug into it for this video, the more it felt like we were peeling an onion. There’s nuance to this, which doesn’t always go over well on social media. So let me be a little spicy … the “solar cost shift” is largely a myth. A myth that has the feeling of truth, which is why it has such legs. But why? And who started it?

Within the U.S, this tension has intensified as solar has become more common. Over the years, the argument that residential rooftop panels worsen the financial burden of everybody else has cropped up again … and again. The thing is, this issue is far more tangled…or maybe interconnected…than you might believe. And there’s a lot more to it than math.

The “cost shift” debate

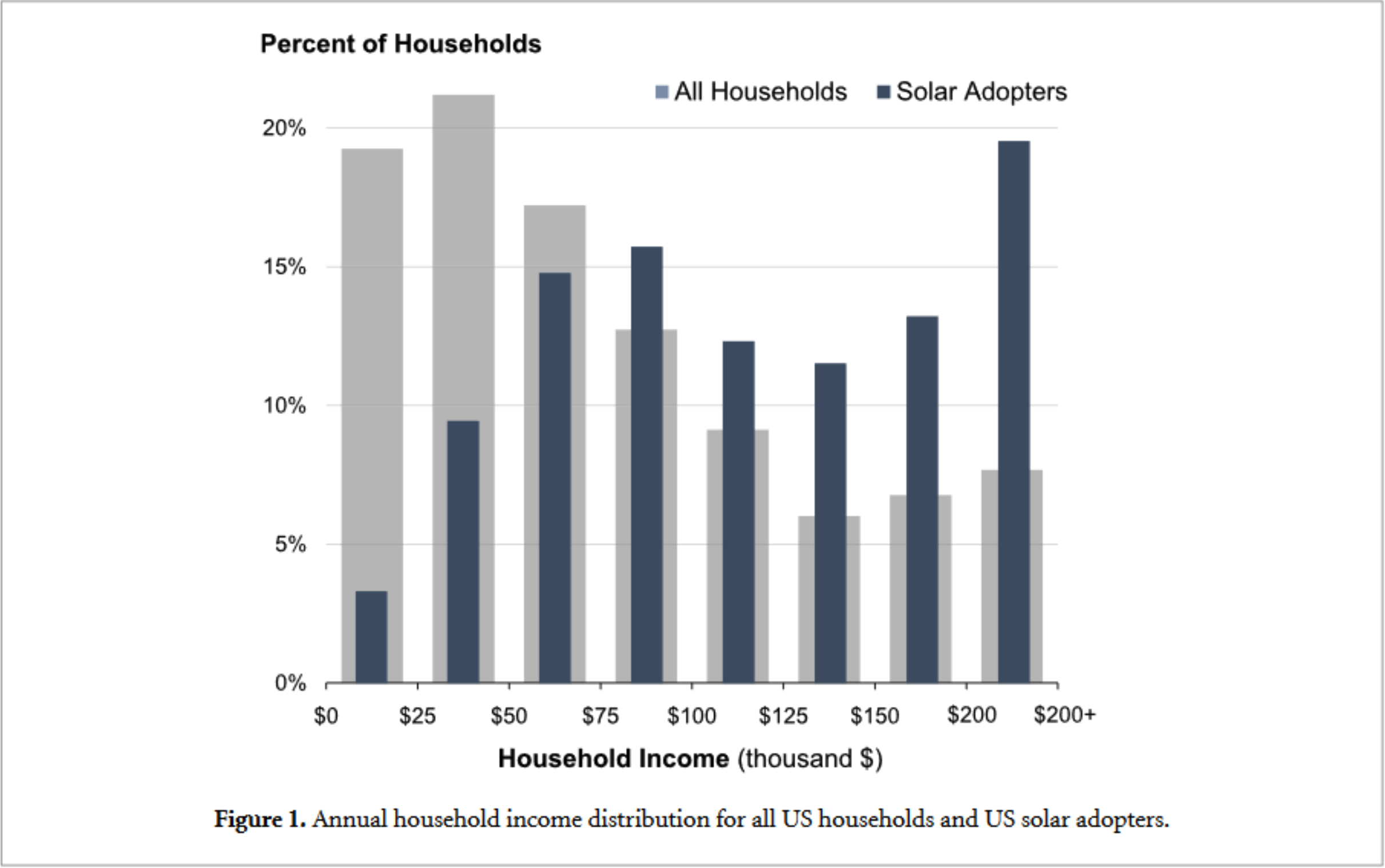

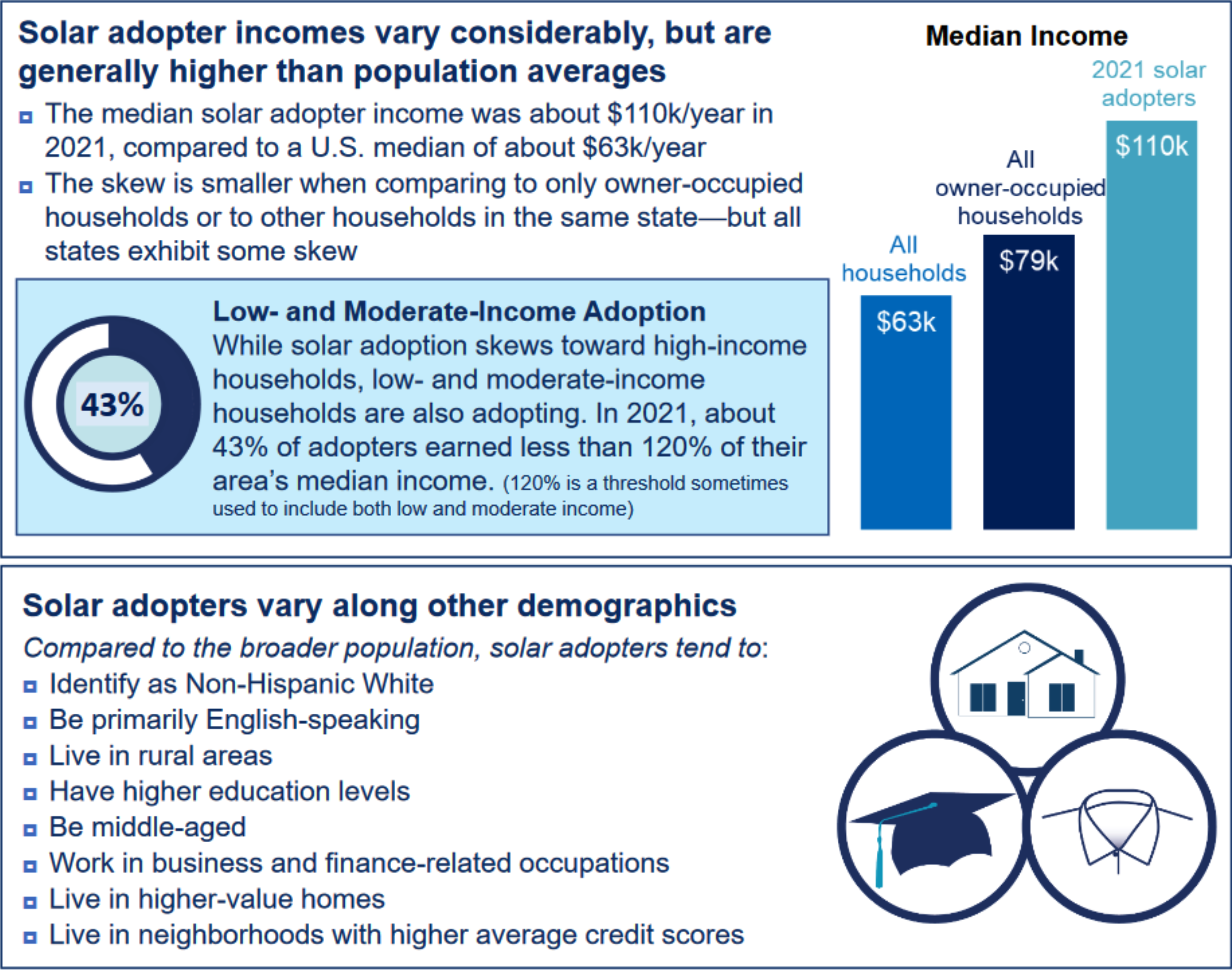

Let’s be clear: the installation of residential solar in the U.S. is inequitable because incomes in the U.S. are inequitable. Similar to a lot of tech, solar adoption tends to reflect existing disparities.1

It skews toward (but is not limited to) higher income, white households.2

This isn’t the full story — and we’ll get to that later — but it makes sense to question how the concentration of solar among the wealthy affects everybody else.

The fundamental conflict of the cost shift, though, comes down to the idea that by using solar panels but remaining on the grid, people can get away with not paying their “fair share” for maintenance of the grid. Consequently, these costs are then “shifted” to those without panels. The overall narrative is that as things stand in the world of residential solar, the rich get richer and the poor get poorer. As the typically wealthier households with panels enjoy the benefits of generating their own power, utilities lose revenue, and the common folk are left to pick up the bill.

The haves vs. the have nots

So, following this logic, does it hurt the grid, and by extension the pockets of your neighbors, to go solar?

That’s a line from an ad run by the Affordable Clean Energy For All coalition, which identifies itself as “organizations representing renewable energy companies, electricity customers, seniors, small-business, faith-based organizations, other diverse community groups and the state’s three investor-owned utilities.”3 I’ll be getting into that coalition more in a bit, but it’s a reasonable-sounding position, right? But it’s vague. What’s a “fair share,” and who decides this?

At a basic level, the problem of the cost shift isn’t technological or even solar-specific. It’s a regulatory and economic conflict that stems from the complicated puzzle of designing fair electricity rates. The rapid influx of renewables onto the grid is creating the necessity for utilities to adapt. Suddenly, customers can now become “prosumers,” or producers and consumers, by installing solar panels. As a result, the grid is decentralizing, and prosumers have their own role to play in the distribution of energy.4 Managing a flow of electricity that can travel both from grid to customer and vice versa requires modernization of infrastructure.56 And modernization of infrastructure requires money.

On top of this, utilities always have to budget for what are known as fixed costs. These are expenses that don’t change regardless of sales — the things that quite literally keep the lights on.7 For example, the network infrastructure itself and the maintenance of power lines. Essentially, utilities advocate for the principle that “fixed charges should reflect fixed costs.”8

That’s the core of the cost shift concept. Under the rate structure of net metering, as it’s known here in the US, or net energy metering (NEM), solar households receive a credit on their bill in exchange for the energy that they generate but don’t use. The “net” in net metering refers to the value you get when you subtract electricity production from electricity consumption.9

Utilities argue that within this system, solar households represent a “cost” in the sense that the rates that they pay, or more specifically, the rates that they (allegedly) don’t pay, makes them more expensive to serve relative to other customers. That missing revenue must be made up, and so utilities have to raise costs for everyone else. Here’s how it’s laid out by a 2018 U.S. Department of Energy study:

“The benefit of bill savings to the customer is the same as lost revenue to

the utility. If and how that lost revenue is captured though different rate designs can affect both

participating (i.e., with PV systems) and non-participating (i.e., without PV systems) customers.”10

Definitely a frustrating thought. Why should one group have to pay more because another group is paying less? Shouldn’t everyone that is connected to the grid contribute to its upkeep? Taken together with the fact that households with rooftop solar are often wealthier, it’s easy to see how net metering and rooftop solar itself has been a point of contention for so long.

These are all valid gripes to have. But positioning solar households as a cost or loss that forces the hand of utilities relies on ideological assumptions. The biggest one? That customers are under an obligation to pay for a service regardless of if they use it: in this case, the electricity provided by the grid. The truth is, whether you offset your costs by installing solar panels or by just turning off the lights more often, you can potentially cause a cost shift. That’s because any reduction in electricity use for any reason can leave a utility making less money than expected. If I buy an energy efficient electric dryer, refrigerator, or furnace, does that jack up the costs of electricity for my neighbors? If I drive my car less, does it raise the cost of gas for everyone else?11

In fact, in a 2017 study by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, researcher Galen Barbose argues that energy efficiency programs have had a much bigger effect on electricity sales than distributed solar. He points out that in 2015, initiatives like appliance efficiency standards knocked down U.S. retail electricity sales by about 14%. In comparison, all the net-metered solar installed through that year only amounted to a 0.4% reduction in sales.12

However, utilities insist that grid use and electricity use are separate things. That is, simply by being connected to the grid, customers’ bills should reflect both their electricity consumption and the utilities’ cost of doing business.13

You have to remember, though, that investor-owned utilities are businesses. And it isn’t the inherent responsibility of consumers to ensure that a business meets its revenue targets, nor should it be. Just take it from Karl Rábago, who’s acted as both a public utility commissioner and a utility executive — in other words, someone who has knowledge from “both sides.” In a 2016 article on net metering, he writes:

“The utility argument is, implicitly, that it had ‘counted on’ collecting an average amount of its fixed costs from all customers through its volumetric energy sales, so customers that use less than they had, or less than the utility assumed, are ‘not paying their fair share’ and ‘avoiding responsibility’ for system costs. Deviations from average or assumed consumption levels do not give rise to a cost for which a utility is entitled to recovery, especially not from the customer who failed to meet the utility’s expected level of consumption.”9

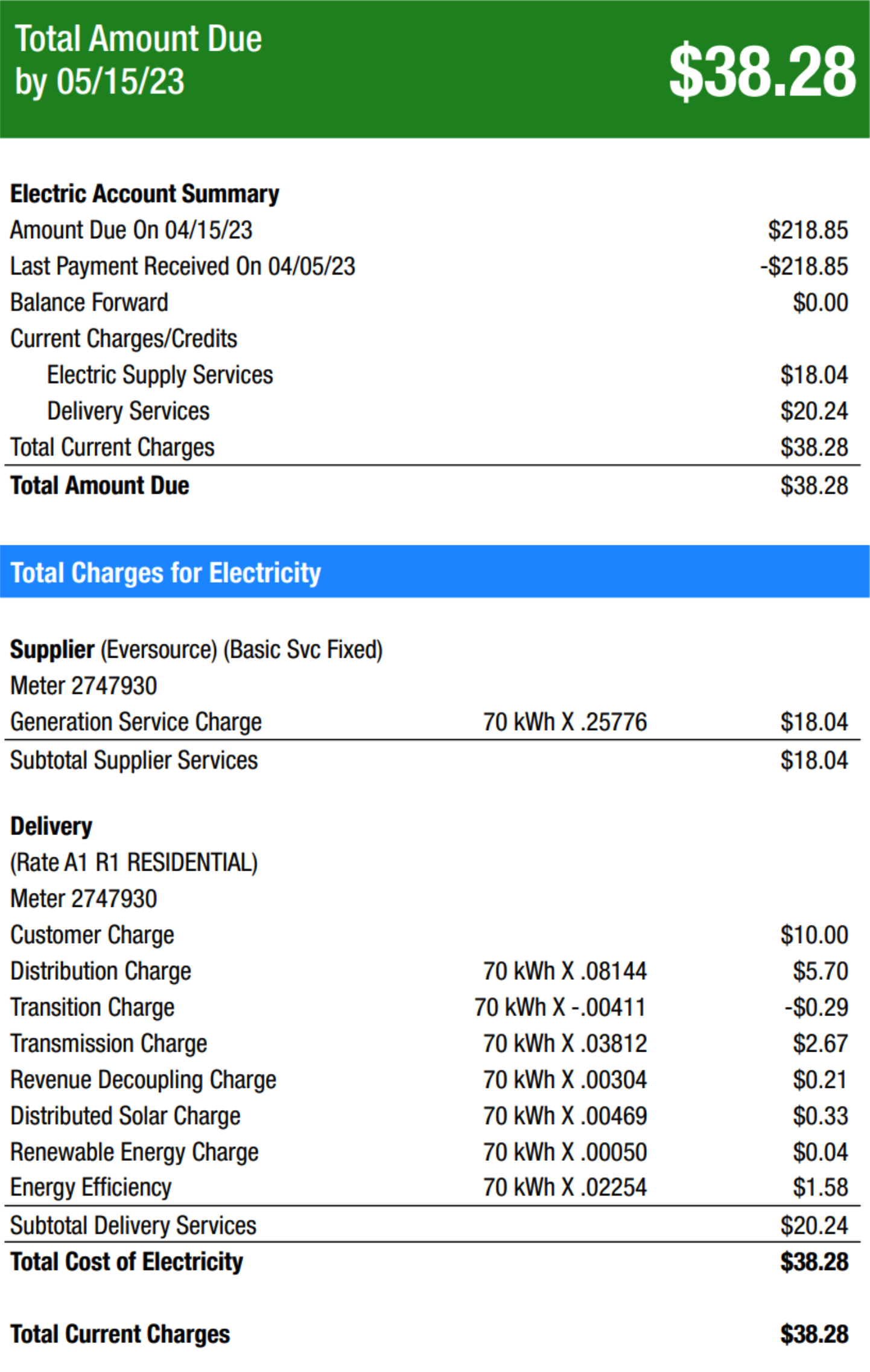

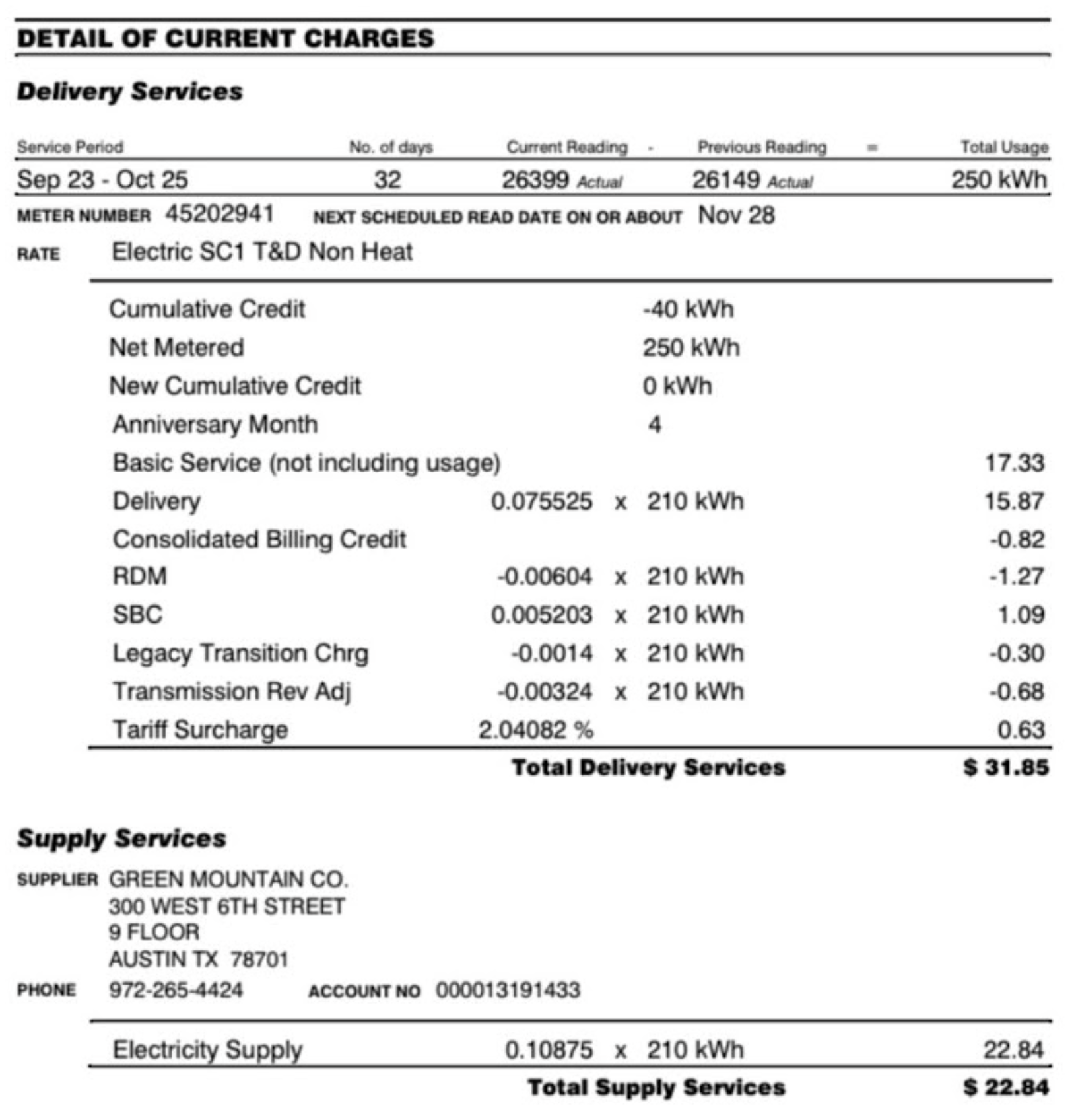

You can see this on my own electric bill. Even though I might produce all of the electricity I use in a given month, I still have a flat “Customer Charge” of $10. Another member of my team has a “Basic Service (not including delivery)” fee of $17.33.

When you look at the big picture, though, this logic doesn’t fly with any other commodity. As pointed out in a 2018 article co-authored by Rábago, we don’t pay “cover charges at coffee shops.”8 A similar metaphor has also been discussed by Ralph Cavanagh, energy co-director and attorney for the National Resources Defense Council:

“Someone explained to me that a minimum bill is like a two-drink minimum in a bar, while a fixed charge is like a cover charge. Everyone in a rate class subject to a fixed charge pays it, regardless of consumption. The resulting revenues are used to reduce charges per kilowatt-hour, which also reduces customers’ reward for saving electricity.”13

But unlike a fancy drink, energy is a necessity to life. It’s not an indulgence, though some may be more fast and loose with their usage. And the ones who conserve the most are subject to the highest rates when fixed costs are conflated with fixed charges. On that point, John Howat, senior energy analyst at the National Consumer Law Center, argues:

“Fixed charges create an intra-class cost shift, from high-volume to low-volume customers. On average, low-income households, the elderly, and households of color use less energy than their counterparts in their rate class. Bigger fixed charges reduce incentives for energy efficiency and customer control over their bills.

For example, Madison Gas and Electric in Wisconsin proposed going from a fixed charge of ten dollars forty-four cents a month to nineteen dollars a month, and a reduction in the volumetric charge. That would result in a 5.5 percent increase in costs for low-use customers, while costs for high-use customers would drop 2.7 percent.”13

See? Accommodating for utilities and keeping things fair for consumers at the same time is just that easy … or … not so much.

And even when rates are unbearable, the vast majority of customers in the U.S. can’t just “take their business elsewhere.” There is the possibility of going off the grid completely…but it’s a bigger investment than installing solar panels alone, which makes it even less accessible. It also makes things worse for everyone by reducing the amount of energy available, and, ironically, spreading these darned fixed costs among a smaller customer base.14 AKA….the exact phenomenon that we want to avoid.

I can use myself as a personal example, here. You have to size your solar PV system to the lowest common denominator, so for me, I’d have to account for the performance drops during the months of December and January. If I do that, I’m going to be producing a ridiculous amount of energy in the middle of May and June. Energy I can’t use! If I’m off-grid, that’s an absurd amount of wasted energy potential that others in my community could have benefited from.

How does it actually affect the utilities?

Incentivizing prosumers to stay grid connected is good for everyone. Everyone including power companies.

Enel, the second-largest utility in the world, is aware of this.15 It considers the number of prosumers connected to its grids an achievement, and in November 2021, the company celebrated reaching the milestone of over 1 million prosumers on its networks across the globe. That represents a collective installed capacity of about 57 GW.45

Over in Australia, which has the highest amount of solar PV per capita in the world, about 29% of the population already has installed panels on their homes or is considering it, according to a national survey conducted earlier this year.1617 Inequities in solar adoption are still an issue, but rooftop solar specifically is helping to drive down demand. Less demand means lower prices and fewer emissions, which benefits everybody. Just this March, a record average output of 2,962 MW from rooftop solar contributed to “the lowest Q1 operational demand in the National Electricity Market since 2005,” according to the Australian Energy Market Operator, or AEMO.18

It’s important to note here, though, that the IEA estimates that based on installed solar capacity, the total theoretical PV penetration in Australia is 15.7% as of 2022 (where the previous survey I mentioned included people considering getting solar). In other countries, this level is even higher. Spain, Greece, and Chile sit at the top of the chart with values of 19.1%, 17.5%, and 17%, respectively.17

Meanwhile, although the U.S. solar market is rapidly growing, the nation is still significantly less involved with solar compared with other countries. Its total theoretical PV penetration is about 5.1%.17 And as described in a 2021 study by the U.S. National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), distributed solar on the whole is underused. More than 95% of the roof space that could accommodate solar is just sitting there, with potential renewable energy ripe for the taking.19

The vast majority of the U.S.’ solar generation is also limited to a few states, with California customers making up about 44% of the net-metered market.20 If California alone were a country, its “PV contribution” would be 25%, according to NREL.21 And when you divvy up the country in terms of the independent system operators (or ISOs) that manage regional portions of the grid, the California ISO (or CAISO) solar generation capacity is the biggest by a wide margin. Solar accounted for about 18.7% of CAISO’s annual load in 2019. Second to California is New England’s ISO (where I live), with solar at 4.3%. This leaves the rest of the countries’ ISOs in the dust. In 2019, solar generation shares everywhere else were at or below 2%.22

Why is this important? Because the potential impact of net-metered solar on electricity prices doesn’t even become relevant until you reach higher levels of penetration, or roughly 10% and beyond. This is why the cost shifting argument is largely a myth. We’re so far away from this possibly being an issue in most locations in the States. Even if you live in an area like California that’s well over that threshold, the impact isn’t as significant or as cut and dry as emotional ad campaigns want you to believe. As described in the 2017 study by Barbose mentioned earlier: “For the vast majority of states and utilities, the effects of distributed solar on retail electricity prices will likely remain negligible for the foreseeable future.”12

This means that the fear of cost shifting, legitimate or not, can’t be extrapolated to the entirety of the U.S., at least not yet. By obscuring the regional context of cost shifting — setting aside the fact that it barely exists — it’s easy to promote it as a pressing issue long before solar has even had a chance to establish a foothold. It’s using it as a boogyman argument. Mississippi, for example, is currently home to less than 1,000 net-metered households.20 It also happens to have solar incentives that are “among the stingiest in the country.” And yet, back in February 2022, when only 586 residential solar systems existed in the entire state, Mississippi Power argued that efforts to further incentivize solar would “be financially shouldered by the non-participating customers.”23 Sound familiar?

So who’s pushing the cost shift argument?

Most people already have trouble just trying to decipher their own bills.24 Mischaracterizing rooftop solar as the enemy of the poor exploits the complexity of ratemaking and regulation. And it has serious repercussions. Recently, concerns about cost shifting have directly impacted California’s public policies. The state’s restructured version of its net metering program came into effect in April, and a peek at the NREL’s Winter 2023 update on U.S. PV shows that prosumers, solar advocates, and environmentalist groups are not happy.25 They argue that with greatly reduced incentives, Californians will ultimately decide against going solar, and that pretty soon the market won’t be feeling so hot.

To make matters worse, decisions like these might actually deepen existing inequalities. Solar adoption is starting to spread out more proportionately across income groups slowly, but surely. As the Berkeley Lab noted in a 2022 report, 22% of all 2021 adopters earned less than 80% of area median income. Another 21% were between 80% and 120% of their area median income.2 If newer solar adopters from these lower income groups don’t receive the same savings and benefits as older adopters from higher income groups, that can effectively “lock in” inequities.2627

Why, then, do investor-owned utilities rail so much against incentivizing rooftop solar? Because their main priority as businesses is money. Distributed generation is emerging as competition and disrupting the natural monopoly.28 And as we’ve shown, both energy efficiency and rooftop solar directly threaten utilities’ profits. This is repeated in plain language again and again over years of research.

But the costs and benefits of solar, or of any renewable generation, are not purely numerical. Analyses that try to quantify the worth of rooftop solar of course rely on a variety of factors. Understanding why some are included and some are downplayed or left out entirely means following the money. Hey, remember that coalition, Affordable Clean Energy For All? The one that included a bunch of community organizations…and three investor-owned utilities? Turns out those three, Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E), Southern California Electric (SCE), and San Diego Gas and Electric (SDG&E), donated a combined $1.7 million to the group in 2020.29 Hmm. Whose best interests do you think they have at heart?

One thing is for certain: Balancing the perspectives of utilities, ratepayers, and regulators when incentivizing rooftop solar is not a simple task. But the motivation behind propagating the myth of cost-shifting is: profit. You can believe what you’d like about utilities’ entitlement to money or lack thereof, but buying into their misinformation doesn’t help you as a consumer, your neighbors, or the planet. This is a confusing enough topic as is, so let’s keep it honest.

- Characterizing local rooftop solar adoption inequity in the US ↩︎

- Residential Solar-Adopter Income and Demographic Trends: November 2022 Update ↩︎

- Coalition List ↩︎

- One million prosumers for the energy transition ↩︎

- The electrification of end consumption – the grid as an enabler ↩︎

- The Future of Solar Energy: An Interdisciplinary MIT Study ↩︎

- Fixed Cost: What It Is and How It’s Used in Business ↩︎

- Revisiting Bonbright’s principles of public utility rates in a DER world ↩︎

- The Net Metering Riddle ↩︎

- Review of Recent Cost-Benefit Studies Related to Net Metering and Distributed Solar ↩︎

- Fighting the Myth of a Solar Cost Shift ↩︎

- Putting the Potential Rate Impacts of Distributed Solar into Context ↩︎

- Rethinking Rate Design: Berkeley Lab’s Discussion with Five Experts ↩︎

- Using peer-to-peer energy-trading platforms to incentivize prosumers to form federated power plants ↩︎

- 10 Biggest Utility Companies Worldwide ↩︎

- Solar power can cut living costs, but it’s not an option for many people – they need better support ↩︎

- Snapshot of Global PV Markets: 2023 ↩︎

- Renewables drive lower prices, record low emissions ↩︎

- The Demand-Side Opportunity: The Roles of Distributed Solar and Building Energy Systems in a Decarbonized Grid ↩︎

- Form EIA-861M (formerly EIA-826) detailed data ↩︎

- Spring 2022: Solar Industry Update ↩︎

- New Berkeley Lab Report Documents Trends in System Impacts, Reliability and Market Value of Solar in the United States ↩︎

- Utilities push back against growth of rooftop solar panels ↩︎

- Consumers Struggle to Understand Their Electric Bills and Rate Options, Survey Finds ↩︎

- Winter 2023 Solar Industry Update ↩︎

- Meta-analysis of the role of equity dimensions in household solar panel adoption ↩︎

- Solar Futures Study ↩︎

- Distributed Generation and Competition in Electric Distribution Service ↩︎

- Coalition received $1.7 million from three California utilities to push NEM 3.0, a rooftop solar ‘killer’ ↩︎

Comments