Wind generates enough energy to produce about 35 times more electricity than the entire planet could even use each day.1 It’s free, clean, and renewable, so why don’t we see more wind turbines used on rooftops like solar panels?

In a nutshell, it’s the blades. More moving parts means more complexity, and you don’t have to worry about that with solar. But what if we could contain those moving parts in a way that’s safer and more efficient? Using a similar design as the “wings” on race cars, Aeromine Technologies has done just that. Its turbine works on rooftops without exposed blades, all while taking up far less space than solar panels. Can the Aeromine make generating wind energy on rooftops a breeze?

Along with other renewables, the use of wind energy is growing. In 2021, turbines contributed about 9% of the utility-scale generation of electricity in the U.S, which is a big jump from less than 1% in 1990.2 Wind also produces a lot more power than solar in general. Last year, wind energy generated more than twice the electricity of solar in the United States.3

As effective as wind turbines can be, they still have their limitations. That’s because the giant propellers that you see dotting landscapes are imposing in more ways than one. Their high upfront costs, maintenance requirements, and effects on wildlife all present significant challenges.

Small wind turbines, or SWTs, are no different, with factors like their sound, height, and aesthetics often hindering their practicality. They can vibrate, which leads to both noise and structural issues. Unstable wind flows can cause turbulence, stressing the turbine’s components. And nearby buildings can affect the wind path, significantly reducing their power capacity.

Basically, there’s a reason why you probably associate wind turbines with rolling hills (or grinding wheat), not gables and chimneys. They’re just not as easy to adapt to rooftops the way solar panels are. We’ve discussed these difficulties in depth in a previous video.

Aeromine aims to solve that problem. The company claims its “motionless” turbine can generate as much as 50% more energy than solar panels using 10% of the space.4 To understand how the Aeromine can accomplish this, though, we need to take a quick step back and explain how conventional wind turbines work.

It all comes down to airfoils. Anything that you need to function aerodynamically requires one: airplanes, helicopters, pinwheels, and of course, wind turbines. In fact, turbines in the U.S. initially used the same airfoil type as airplane wings before scientists developed blade-specific ones.5 Without the feather-like shape of airfoils, we wouldn’t be able to conquer the skies.

The purpose of an airfoil is to make physics work for you. Both turbines and airplanes want more lift than drag, so they use airfoils to take advantage of the Bernoulli Effect. This refers to how gasses and liquids flow around an object at different speeds. A slower-moving fluid (like air) will build up more pressure than a faster-moving fluid, and this forces objects toward the faster-moving fluid.

The layout of an airplane wing causes air to flow faster over the top side and slower on the bottom side.[^nasa]This results in the bottom side producing the higher air pressure needed for the lift that gets planes off the ground – and the blades of turbines moving. And as the rotor of the turbine spins, it powers a generator, producing electricity.6

In the case of auto racing, though, you don’t want your car to go flying. That’s why both the contours of the car’s chassis and the “wings” that engineers stick on its surface are upside-down airfoils.[^nasa][^wrc] As the air underneath the car moves faster than the air above it, negative lift, or downforce, pushes down on it. This downforce stabilizes vehicles and allows them to maintain speed as they turn corners.[^nasa]

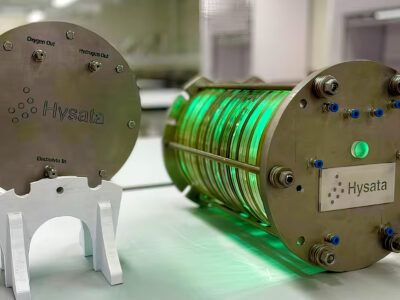

What does this have to do with Aeromine? Well, the airfoils on race cars are stationary, and so are “Formula 1” style airfoils that power the company’s turbine. Looking at it from the exterior, there’s no exposed moving parts. Instead, two vertically mounted, hollow foils stand opposite each other with a space between them. This creates a low-pressure zone, and as wind flows through the space, it’s drawn through perforations in the wings. A short pipe then leads the captured wind to a fully enclosed turbine located at ground level.7

Several of the weaknesses that hold typical turbines back are addressed by the structure of an Aeromine. Because the turbine-generator is housed inside, it’s both protected from extreme weather and inaccessible to people and animals, eliminating a major safety concern.7The company claims that the Aeromine is silent and that its lack of exposed moving parts means less maintenance.8It also can operate with wind speeds as low as 5 mph (8 kph). In contrast, conventional turbines need wind speeds of 9 mph (15 kph) or higher to operate.9

How do Aeromines compare to solar? Right now, the answer is a little vague, or at least not yet verified. Its website claims that “a single Aeromine unit provides the same amount of power as up to 16 solar panels,” but doesn’t offer any specs.8 We do have a rough idea of what the Aeromine might be capable of, though, because the company participated in the 2021 AFWERX Reimagining Energy Challenge, a U.S. Department of Defense crowdfunding program. At its “virtual booth,” Aeromine rates its turbines for 5 kW and estimates that each one could produce 14.3 MWh annually.10

To put that into perspective, a 5 kW rating is comparable to the power of the average 21-panel rooftop home solar system.11 These types of setups generally produce about 4.5 MWh of electricity a year.12

As for costs, a 2019 analysis published by Aeromine in collaboration with Sandia National Laboratories and Texas Tech University estimated that the turbine can be installed at $2,400 per kW.7By comparison, the average cost of constructing solar panels of all types was $1,655 per kW in 2020.13However, only time will tell how closely the actual cost of the Aeromine matches the company’s estimate.

Let’s be clear, though: Aeromines are not the kind of turbine you’ll see on a single-family home. In the company’s own words, they’re intended for “large, flat rooftop buildings” like warehouses, data centers, and big-box retail stores.8 And remember, the airfoils are stationary. Their angle won’t change even when the wind’s direction does, so they’re best suited for locations where there isn’t much variation in the wind’s direction.14

Aeromines aren’t commercially available yet; the company hopes to have them on the market by 2023. However, one unit is currently undergoing testing on top of the roof of a BASF Corporation manufacturing plant in Wyandotte, Michigan.14 In theory, a fully deployed Aeromine system would look like 20 to 40 turbines lining the edge of the building in a row, spaced about 4.6 meters apart and facing the predominant wind direction.9 11 The company emphasizes that because the turbines leave room for panels, they’re “complementary” to solar, allowing for power production to continue after sunset or on cloudy days.15

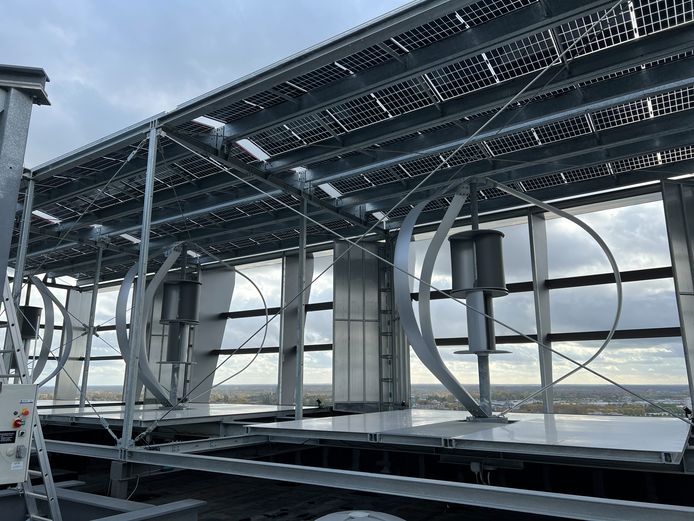

Luckily, we don’t have to wait for the Aeromine to witness the potential of rooftop wind energy. The Dutch company IBIS Power is already demonstrating the benefits of combining solar panels with small turbines with a form of installation called a “PowerNEST.” PowerNESTs are specifically designed to blend in with the existing architecture of a city. They require a flat roof on a building with a minimum of five floors.16

Attempting to harness wind energy within a metropolitan area usually isn’t logistically possible. It’s not like we have spare kaiju that can install massive turbines on top of skyscrapers for us. But PowerNESTs integrate small turbines, funnels, and solar panels into what IBIS refers to as a modular “kinetic sculpture” to maximize the amount of electricity a single roof can produce. In each “nest,” turbines and funnels lie beneath a raised platform of bifacial solar panels. The company claims that this arrangement provides as much as six times more energy than solar panels could generate alone.16

How is this possible? With more physics — this time the Venturi effect. Have you ever held your thumb over the end of a garden hose while the water was on and noticed the flow speed up? That’s the Venturi effect in action.17As a fluid moves through a constricted space, like a funnel, its velocity increases.18

IBIS claims that the PowerNEST’s use of the Venturi effect accelerates the wind’s speed by 140 to 160%. Its turbines can also turn in wind speeds as low as about 4.5 mph.19

Meanwhile, the solar panels are optimized through their placement on a raised platform, which means covering a bit more than the entire area of the roof, rather than only about 40%.20Plus, the wind cools the solar panels as it travels below them, which can translate into a 10 to 25% boost in efficiency.21 IBIS makes it clear that the PowerNEST is not simply wind and solar power forced together, but an integrated design that brings the best of both worlds together in harmony.

Europe saw the construction of the first commercial PowerNEST in 2019, and so far, the results seem promising in terms of how well it gets along with its neighbors.22According to a 12-month study of a demo version of the PowerNEST, an installation atop a residential complex in the Dutch city of Utrecht caused no noise or vibration in the apartment below it. The building’s residents didn’t have any complaints, and the company states that it discovered zero bird or bat casualties inside or near the system.23

This past July, IBIS constructed a PowerNEST atop Haasje Over, a 70-meter residential tower in the Dutch city of Eindhoven. With 296 solar panels and four turbines, the company estimates that the modules will generate “no less than 140 MWh a year.”24 IBIS is in the midst of installing more PowerNESTs in the Netherlands and Belgium, and the company’s CEO, Alexander Suma, has also expressed interest in major U.S. cities like Boston and New York.22

Concepts like the Aeromine and the PowerNEST show us that small wind turbines can not only be effective independently, but even more impactful in the way that they can diversify our renewable energy sources — meaning more energy generation, more of the time. It’s like peanut butter and chocolate: Why have one when you could have both?

- How Do Wind Turbines Work? ↩

- Total U.S. electricity generation from nonhydro renewables is increasing ↩

- Electricity Data Browser ↩

- Aeromine Technologies’ Press Release ↩

- Advanced Airfoils for Wind Turbines

[^nasa]:Racing Physics ↩ - How a Wind Turbine Works ↩

- A Novel Energy-Conversion Device For Wind and Hydrokinetic Applications ↩ ↩ ↩

- Aeromine Technologies Website ↩ ↩ ↩

- New motionless tech harnesses wind energy from rooftops ↩ ↩

- Solution Name: AeroMINE: Motionless, Simple, Robust, Deployable Wind Technology ↩

- Rooftop wind system delivers 150% the energy of solar per dollar ↩ ↩

- Is a 5kW Solar System Suitable For Your Home? ↩

- Average U.S. construction costs drop for solar, rise for wind and natural gas generators ↩

- These Mini Wind Generators With No Spinning Blades Can Power Homes and Buildings ↩ ↩

- R&D 100 Winner 2021: AeroMINE — Stationary Harvesting of Distributed Wind Energy ↩

- IBIS Power ↩ ↩

- The Venturi Effect ↩

- Venturi Effect ↩

- PowerNEST Full Roof Integrated Wind & Solar Energy System ↩

- IBIS Power completes first full roof PowerNEST installation ↩

- Why Install PowerNEST? ↩

- Why aren’t there more small wind turbines on buildings? ↩ ↩

- Final Measurement Results PowerNEST DEMO at Henriettedreef Utrecht ↩

- PowerNEST installation day at Haasjeover in Eindhoven 2022 ↩

Comments